(Article on ibogaine as it appeared in the July 2000 edition of Focus magazine)

Beneath a brilliant vault of stars, a young man is sitting on a rug somewhere out in the South African veldt. But he only has eyes for the extraordinary parade of images inside his head. There is a tremor to his legs that makes it hard to stand and he’s regularly gripped by waves of nausea. However, none of that matters.

For several hours all his attention has been focused inwards, on scenes from his childhood, many of them painful… his mother shouting at him the time his father left: he sees their flushed faces, hears their harsh words, feels his own fear and anger. It’s only a memory, but it’s a turbo-charged memory. Think holiday snap compared with a film shot in Imax.

He’s taken a drug, of course, but one that is not illegal. The sheer intensity of the ibogaine experience is something that even the most voracious drug-taker would only want once or twice in a lifetime. In fact he is taking it as a one-off cure for a heavy heroin habit. Not only does ibogaine give you psychological insights that normally come only after months of therapy, but it takes away all craving for the drug of choice – heroin, cocaine, alcohol, nicotine.

The man on the blanket is one of scores of addicts who, over the last few years, have taken ibogaine while in the grip of a $l00-a-day habit, and emerged 30 hours later, free of a desire to take it and with none of the dreadful symptoms of withdrawal. A group calling themselves INTASH (International Addict Self-Help) are enthusiastic about the drug. “In the world today there is no substance as effective in combatting opiate narcotics, stimulants, alcohol and nicotine addiction as ibogaine. Being prepared for treatment with ibogaine means being ready and willing to take a physical and spiritual leap forward,” said a spokesperson.

Ibogaine is one of several alkaloids found in the West African shrub called Tabernanthe Iboga. The first reports of it came from French and Belgian explorers in the the last century. “ln small quantities it is an aphrodisiac and a stimulant of the nervous system,” wrote one traveller in 1864. “Warriors and hunters use it constantly to keep them awake during the night watches.”

These travellers took it home, which is why, like coffee or cocoa, it was first used in the West as a tonic. French chemists crystallised it at the turn of the 20th century (about the same time cocaine was crystallised from cocoa) and it was used as a treatment for sleeping sickness and for convalescents. Pills containing 8mg of ibogaine were sold in France in the 1930s under the Lambarene trademark. It was claimed they got rid of fatigue and improved appetite.

The iboga was initially used by the Mitsogho, a tribe from the area of Africa that is now part of Gabon. The Baka pygmy tribe of the Congo basin are also thought to have been among the first to learn the use of the plant. For 300 years it has been an integral part of the once-in-a-lifetime rite of passage by which boys become men and any males who do not complete this initiation test will forever be branded as girls. [Editor’s note: I don’t think this is true. Women are initiated same as men as far as I am aware – Nick]

And it certainly is a test. Candidates must chew about 100g of iboga root shavings over a period of eight hours. They are washed and purified in the river and when their legs give out they sit in the chapel and gaze into a mirror. “Behind them sit their mothers or fathers of iboga, calming their anxieties and listening carefully to their excited mumblings as the iboga works upon them,” wrote one observer. “They may already be experiencing a sense of departure from self and of visionary encounter. Their mumblings may convey important information to the entire membership.”

The guide who stayed with the man on the blanket through every moment of his inner journey was Dan Lieberman, a South African ethnobotanist but never an addict. For $3000 he will take you on a 10-day initiation trip of your own. I meet you at the airport and from that moment you don’t have to do anything,” he says. I stay with you all the time. When you take the ibogaine you are in a super-aware state between sleeping and waking. Your body is in a deep coma but your mind is completely aware.You work through all sorts of past traumas. Some people do it for self-discovery, others to beat addiction.”

Lieberman first encountered ibogaine when he was studying Bwiti religious initiation rituals in Cameroon. These rituals involve consuming large amounts of bark scraping from the iboga root. Initiates have described their extraordinary experiences: they encountered menacing animals, met with higher spiritual entities and talked to their ancestors. At the end, many said they had a sense of the whole course of their lives.

While Lieberman works on his own and gives his client the actual plant material, a more high-tech – and thus expensive – anti-addiction programme using the ibogaine extract is available from Dr Deborah Mash. Professor of Neurology at the University of Miami School of Medicine in Florida.

Another key player in the ibogaine story, she is the only academic to have run preliminary trials on humans at a university, although she has never taken it or any illegal drug. She has a state-of-the-art medical set-up on St Kitts in the Caribbean, where, for $10,000, you can get proper screening, nurses, heart monitors and a Harvard professor who oversees the proceedings and will draw up your own personal rehabilitation programme.

“We have had people who have been on really high doses of methadone, which is a horrible drug to kick,” says Mash. Seventy two hours later they are free of it and swimming in the Caribbean. It is an amazing treatment.”

Mash has now treated around 70 addicts – ‘our first one is still clean two years later” – and a summary of 30 cases was presented at a landmark conference on ibogaine in New York last November. Delegates heard that 25 of these 30 addicts had had no further cravings, not even any withdrawal symptoms after 24 hours. “lt doesn’t work for absolutely everyone,” says Mash, “but it is a hell of a lot better than anything else we’ve got.”

Her view is echoed by someone in the front line of the fight against drug addiction and who believes in ibogaine’s potential. “The normal treatment for addiction is individual and group psychotherapy plus methadone,” says Patrick Walsh of the US National Probation service in New York, “but we are not making good progress. If we can keep 10-20 % of youngsters off drugs just for the time they are on probation, we figure that’s a success.” British figures, for all the talk of a new drugs tsar, are not much better

The use of ibogaine as a cure for addiction is largely down to the efforts of a New Yorker, one-time film student Howard Lotsof. In the ‘swinging Sixties’ he was a heroin addict until someone handed him a mysterious drug, promising it would get him really high. Lotsof had a remarkable time, seeing visions and being taken back through his personal history, but what really amazed him was that afterwards his craving for heroin had vanished.

As reported by those who have taken ibogaine, he suffered no withdrawal symptoms – he didn’t have to make an effort of will, he simply didn’t want it any more. Wondering if it was a fluke, he persuaded six of his addict friends to take it. Five of them also came off heroin, and stayed off. There followed a period of ‘informal’ testing to discover the optimum dosage and conditions under which it should be taken before, in the mid-’80s, he patented ibogaine as a cure for heroin, cocaine and alcohol addiction.

So how does ibogaine produce such a remarkable range of effects on the body? Unfortunately, the most straightforward answer at the moment is that we don’t know exactly. Not least because the research into ibogaine has been done on laboratory animals, which reveals little about the brain mechanisms involved in intense visions of childhood. Another problem is that, despite years of research, we don’t even really know why people become addicted in the first place.

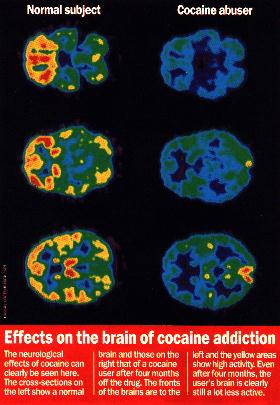

However, we do know that ibogaine reduces the amount of dopamine, which is one of the key chemical messengers in the brain. Research has shown that everything we find enjoyable – from Morris dancing to sex – produces a burst of this chemical that then hits one of the brain’s pleasure centres, called nucleus accumhens. It is thought that all addictions – cocaine, heroin, nicotine, shopping – trigger such a dopamine rush to satisfy the addictive cravings.

Researchers at Albany Medical College in New York state, such as Professor Stanley Glick, have made rats addicted to cocaine or morphine and succeeded in training them to press a bar in their cage to get supplies of the drug. They found that an injection of ibogaine decreased the amount of morphine the rats gave them by 50 %. Like humans, some almost gave up completely, whilst others needed several doses. One curious finding was that while ibogaine reduced the amount of activity by male rats on cocaine or amphetamines, it actually speeded up the female rats on the same drugs. But addiction is obviously not just a mechanical matter of having a dopamine problem. Nearly everyone in the ibogaine network stresses the importance of following up an ibogaine experience with some sort of counselling. “What ibogaine does is to buy a window during which the resistance of the body’s defences is softened,” says US therapist Sarah Emanon. “After taking ibogaine the person doesn’t crave the drug and feels great. But if they don’t make use of that time to consolidate what they have discovered, they are very likely to relapse.”

Both the people who have studied the chemistry of ibogaine and those who are interested in what it does psychologically conclude that it somehow resets the brain and mind so they work more effectively. It is almost as if ibogaine overwhelms the system psychologically and emotionally with the hallucinations,” says Emanon, “so the person cannot behave or interpret what is happening using the old destructive patterns.”

After researching ibogaine at a molecular level, Alan Leshner, director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse in Maryland, concludes: “There is evidence to suggest that ibogaine treatment might result in the ‘resetting’ or ‘normalisation’ of neuroadaptations related to sensitisation or tolerance induced by addiction.”

Whatever the brain mechanisms turn out to be, ibogaine involves a dramatic change in the approach to addiction. Previous attempts to fight drugs with drugs have either involved trying to block the effect of the illegal drug or find a substitute, but none have been effective. “Ibogaine presents a potential new strategy for treating addiction to diverse drugs classes,” concluded Professor Piotr Popik of the US National Institutes of Health, Maryland in a major review of the scientific literature on ibogaine.

So why isn’t ibogaine part of every drug rehabilitation program, in stead of, for the most part, being administered surreptitiously in hotel rooms in America and Amsterdam? “Although it does have remarkable properties,” says Professor Glick, “from the point of view of the medical establishment there are problems with it.”

“The original work on it was done by an ex-hippie and one-time drug addict with no background in pharmacology. It’s a naturally occurring plant alkaloid, which no one knows how it works – and it is a powerful hallucinogen.”

The image problem aside, such a remarkable cure for addiction should be a big enough money spinner for the pharmaceutical companies to snap up. Glick, one of the organisers of the New York conference, explains why it isn’t. “Pharmaceutical firms are not very interested in such anti-addiction drugs. Addiction has got obvious negative associations and there is not nearly as much money there as you might think. We only spend about $65m on developing addiction pharmacotherapy, which is a fraction of the estimated $200 – $600m average cost of bringing a single new drug to market.”

One of the big mysteries of ibogaine is: how can a single dose apparently keep on working in the body, months after it should have been broken down by the liver and evacuated? Dr Mash now thinks she knows the answer.

It seems that the liver turns ibogaine into something called noribogaine, which stays in the body and behaves like a Prozac implant, raising the levels of serotonin in the brain and keeping patients happier and free of cravings. Mash currently plans to develop a noribogaine skin patch to help reformed addicts stay clean.

Panels

Ibogaine and regression

Because of its ability to stimulate memories of vivid early experiences, ibogaine has attracted the interest of therapists who are particularly interested in regression. There have been no formal studies, but reports vary from positive to very negative.

Therapist Sarah Emanon is someone who has found it very valuable. “I gathered pictures from my childhood and I pored over them before the session. When the effects of the drug came on, the emotions of the people in the pictures – my father and mother, and my adopted father and mother started popping out at me.”

Going back: “I saw that my father was very well armoured. I remembered being a little girl and trying ‘to get to him, but I couldn’t reach this person. Then I saw my current partner and saw how I couldn’t get to him either. And it just went boom, boom, boom – all the way back to my father.”

“Then, I went back even further, to being with my adopted mother as an infant while she was holding me. Then I smelled her, and it didn’t feel right. I didn’t want to be near her. I was trying to get away but I didn’t know how to hold my head up. That’s where I realised I retreated into myself.”

“So here I am focusing on all the people in relationships, but there is no communication either way. And I saw myself picking people who can’t come out of themselves because I can’t come out of myself. This was the beginning of owning my own process rather than projecting it onto others.”

Ibogaine trip – a personal accountWhen I ate iboga, I found myself taken by it up a long road in a deep forest until I came to a barrier of black iron. At that barrier, unable to pass, I saw a crowd of black persons also unable to pass. Suddenly my father descended from above in the form of a bird. He gave to me then my iboga name, Onion Messenger, and enabled me to fly up after him over the barrier of iron.As we proceeded, the bird who was my father changed from black to white – first his tail feathers, then all his plumage. We came then to a river the colour of blood, in the midst of which was a great snake of three colours – blue, black and red. It closed its gaping mouth so that we could pass over it.On the other side there was a crowd of people all in white. We passed through and they shouted at us words of recognition until we arrived at another river, all white. This we crossed by means of a giant chain of gold. On the other side there were no trees, but only a grassy upland.Return or die. On the top of the hill was a round house made entirely of glass and built on one post only. Within I saw a man. The hair on his head piled up in the form of a bishop’s hat! He had a star on his breast, but on coming closer I saw that it was his heart in his chest beating. We moved around him, and on the back of his neck there was a red cross tattooed. He had a long beard.Just then I looked up and saw a woman in the moon – a bayonet was piercing her heart, from which a bright white fire was pouring forth. Then I felt a pain in my shoulder. My father told me to return to Earth. I had gone far enough. If I went farther I would not return.Jerome Burne – Focus Magazine, July 2000